John Lopresti, former researcher from Agriculture Victoria, introduces stonefruit cultivar performance for export, part of the Serviced Supply Chain project

So the benefits to growers and exporters having this cultivar specific storage information is that they can make marketing decisions about specific cultivars and in some cases decide, for example, a white page can only be exported by air freight, which is obviously of much shorter duration than sea freight.

Whereas other cultivars such as yellow nectarines, or even some white nectarines have a much longer storage potential and thus are amenable to sea freight storage. And the real benefit here is that grower exporters are reducing the risk of storage disorders in their fruit over that long, export period, particularly during sea freight, and providing their customers with, with a higher quality product.

John Lopresti from Agriculture Victoria discusses storage behaviours of selected stonefruit cultivars. August 2021

Can we reduce the risk of storage disorders in nectarine and peach after sea freight?

Graph 1: Storage at 2°C

Graph 1: Storage at 2°C

Graph 2: Storage at 8°C

Graph 2: Storage at 8°C

Recommendations for cultivar storage potential should be considered general guidelines:

So today - cultivar performance. Some recent work with some work with recent cultivars, particularly white fleshed, nectarines and peaches. The potential for storage disorders and how it varies with cultivar or variety.

I'll use those interchangeably. Impacts of temperature management during exports. Some examples of commercial simulations we've done for air fright . We've conducted for air freight and sea freight. And then predicting fruit softening using temperature in storage duration. And finally, I'll demonstrate a simple stone fruit shelf life prediction model.

Okay, so harvest and storage performance issues, basically it comes down to three or four factors, and obviously the key one, I believe is variety. Because we've tested probably 12 to 15 different over the three and a half years, and that can behave quite differently, even under the same temperature and storage conditions. Some of them much more susceptible to storage disorders as in flesh browning and mealiness during longterm storage or during a sea freight export. And the reality is this, although we'd probably covering familiar ground in terms of some of our trials, there is very little information about a lot of the new varieties that we're growing specifically for export and the domestic market.

I don't think we're treading new ground, because we really don't know a lot about these cultivars in terms of how they perform after harvest. So we've found some, and you'll see, we found some interesting results. The other issue is that basically a lot of these varieties, we are sea freighting and the reality is that sea freight is taking between three and four weeks, just the sea freight component.

It's not three weeks, it's not 21 days. It's generally well beyond that before they arrived at the importer, overseas. So these cultivars, some of these are unlikely to actually be sea freighted successfully because of these storage disorder issues. And then you might have the importer storing the fruit for one week or more waiting for the right time to market the fruit.

So that is a major issue that duration from harvest right through to when they arrive with the importer can be beyond four weeks. Then we've got harvest maturity, and the inherent variability of the fruit you're harvesting. And this is an example here, just in terms of sugars, that harvest for Majestic Pearl. And this is a graded, this is fruit that has been graded, is ready for export. And you can see the variation in soluble solids, and we've been finding that up to 25% of fruits, in a particular cultivar, is lower than what we would term acceptable in terms of sugars. So there is, you can find quite a bit of variability evening in soluble solids and sugars.

And the other issue that we've had is limited temperature monitoring, particularly before export and after exports, so during importer storage and beyond, into retail. And Glenn's been doing a lot of work in that area, over the last few years.

So I'll vary briefly mentioned harvest maturity because Christine will be going into it, but we've done a lot of work looking at the effects of harvest maturity. So, there's a diagram of September Bright testing and categorizing a batch of fruit by the actual physiological maturity, so this would be considered the onset or commercial maturity, harvest maturity, unripe, I believe. Obviously you can't tell any difference between them visually, but physiologically, they're quite different. And this is the type of data we collect- storage over six weeks at two degrees. And then after each storage period, ripen the fruit and these are the three maturities. So what we determine unripe fruit, commercial maturity, and then overripe fruit, and you can see the difference in behaviour as we move along the storage period. And I said Christine will be talking much more about that specific cultivars and optimal harvest maturities. And then Glenn will be mentioning, will be discussing in detail, export temperature monitoring. And some of, very generally what we found is with air freight we do get variable temperatures over that actual air freight period of 24 to 48 hours. So variable temperatures and spiking temperatures, eight up to 12 degrees over that short period. And we don't really know the effect of these short and high temperature spikes. Although in a little while, I'll show you what the effect is likely to be because we've, we've conducted air freight simulations and you used a few high temperatures to see if there's any impact on quality later on. And then sea freight, the sea freight leg, because of this infestation protocols is always good, below three degrees for 21 days and beyond, but the major issue we found is that see freight leg is taking way too long, greater than twenty seven days and can be up to 35 days between harvest and getting to the importer, which is, in my opinion, a little bit ridiculous. We can't expect the majority of cultivars we're growing to actually store that long and then ripen them properly. That's a major issue.

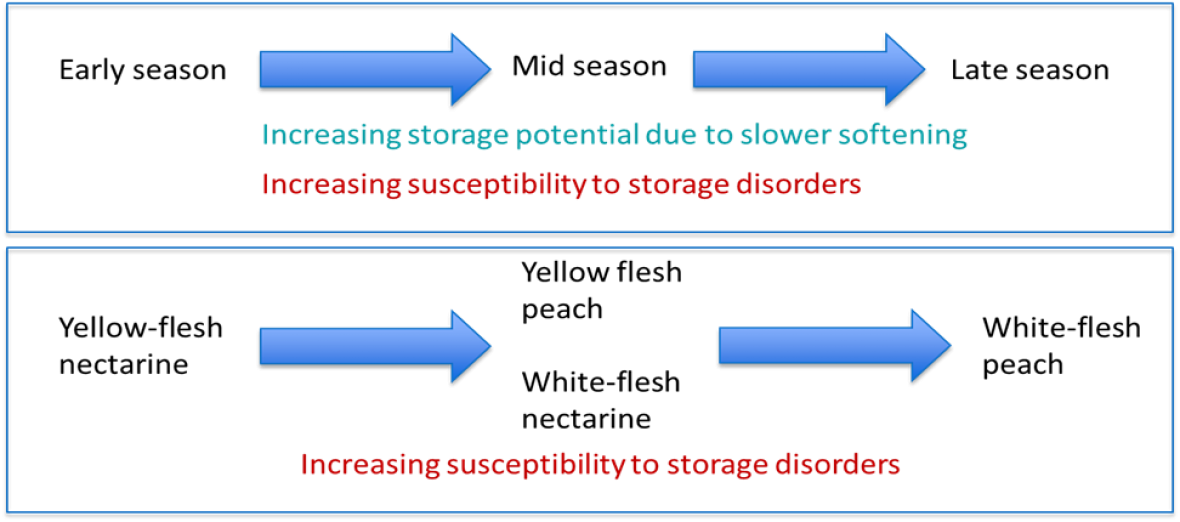

Okay, so let's move on to what we're going to focus on today and in general, what we've found, and this is probably common knowledge in terms of the general storage behaviour by fruit type and variety. If we look at early season varieties, then mid season and then late, you tend to get increasing storage potential, due to reduced softening. So the early season varieties tend to soften more quickly even at lower temperatures. And I'll show you some data demonstrating that, but you also get increasing susceptibility to storage disorders as you're moving to later into the season. With, in terms of type of stone fruit, well the white flesh tend to be, have less storage potential, than your white flesh peach. Then somewhere in the middle, I categorize the yellow flesh peach and white flesh nectarine as to having some average storage potential. And then your yellow flesh nectarine tends to store, have greater storage potential. But again, even though we know that white fleshed varieties tend to be susceptible to storage disorders, in fact, the later varieties, whether they're white or yellow, again, tend to be a little bit more susceptible. And then you've got factors like tree age in the order, whether young trees or older trees. Orchard climate warm weather versus cooler climate orchards or regions. Meltingness versus non melting, although we don't really, as far as I know, really grow melting varieties anymore. So there are other factors, but these are the general, what we've generally observed.

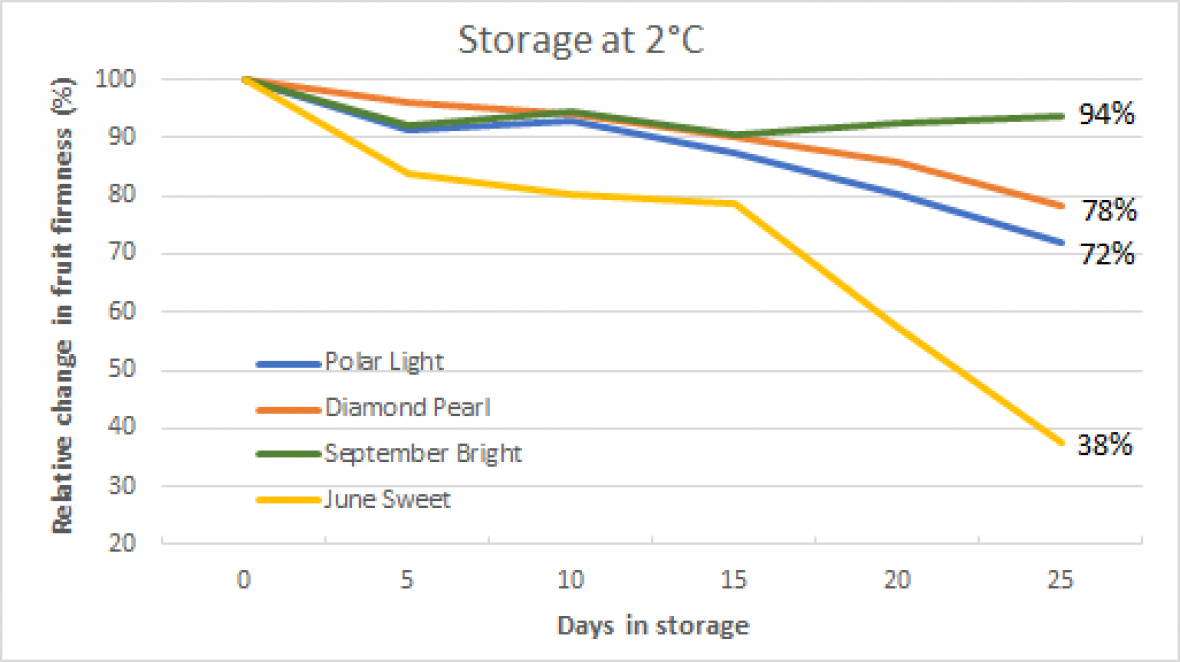

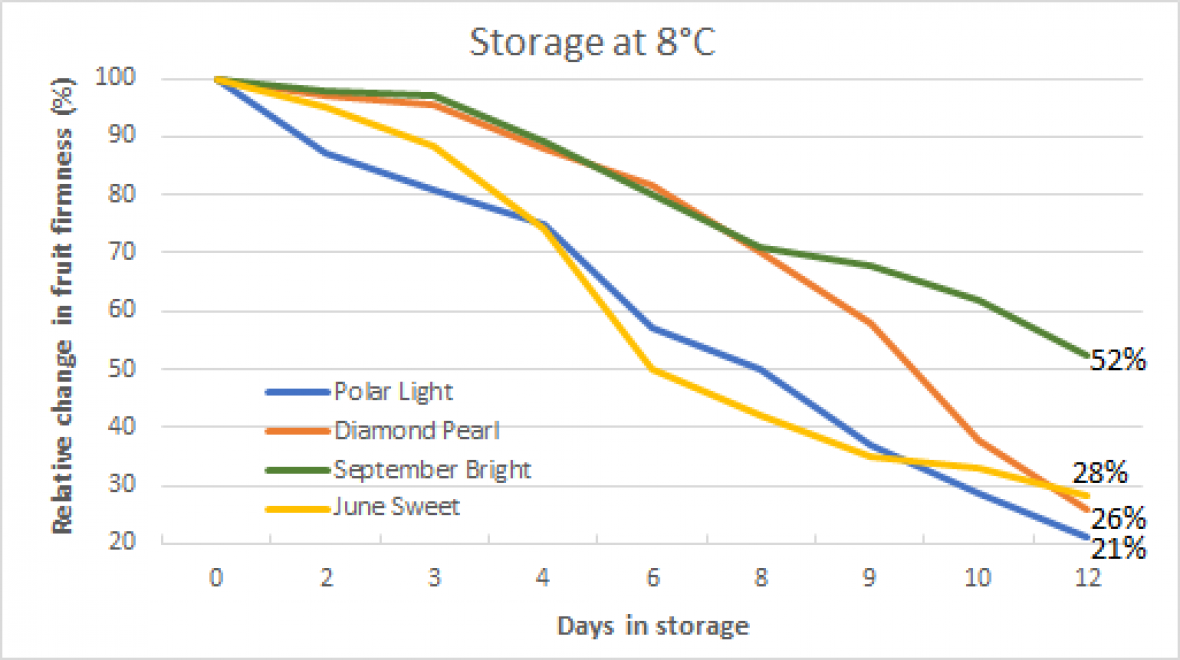

Okay. So in terms of storage behaviour, among varieties, here we have four varieties. So we've got the table here. Very early yellow nectarines - June sweet, an early white nectarine - Polar Light, an early white nectarine - Diamond Pearl, and a mid yellow nectarine or mid to late yellow nectarine - September bright.

These are the harvest firmness when we ran these trials, so they're all around the six to six and a half kilos at harvest. What I'm plotting here is the change in fruit firmness from these initial harvests during storage, so days in storage up to 25 days here. This is storage at two degrees and the final, and you can see how the fruit softens or how much fruit softens from the start. If we call the harvest firmness a hundred, then you can see the differences in how the different varieties behave. June Sweet you lose 60% of initial firmness over that storage period of two degrees. Whereas for example, September Bright, there's very little change in firmness, and then you've got your white, early white nectarines are somewhere in the middle. So you can see what a large difference cultivar or variety makes to storage potential, even at this sort of close to optimum two degree storage period. Down here, we've got storage at eight degrees, which is obviously far above optimum, but just to demonstrate the same effect. Same 4 cultivars. Yes, you lose 50% of your firmness after 12 days in September Bright, but it's the other earlier varieties, whether they're white or yellow fleshed, you're losing 75% of firmness at 8 degrees, which is to be expected. But again, to demonstrate there are differences purely biased on variety. So it's very clear that variety is one of the key aspects of determining storage potential. And although we've done work for a number of varieties, I think there's still a lot of work to be done, to get, to really understand how these varieties perform and which ones are limited, in terms of export. The other thing we've found in a lot of our work is storage disorders, mainly flesh browning and mealiness caused by chilling injury, which is usually related to storage duration. And for example, this photograph is of majestic Pearl, and here we've got a sea freight export simulation. The actual sea freight was 28 days. We conducted at Agribio centre in our cool rooms, and we had different importer storage temperatures. So once the fruit arrived, the simulated importer storage at four, eight and 12 degrees. But as you see, at the end of sea freight and after, there was no sign of flesh browning, but after four days of importer storage, four to five days, you already got started to get this kind of browning occurring. And it really didn't matter, end of retail and then It was flesh browning consistently. And this picture down here is Flavoured Pearl, which is a white nectarine that comes in before Majestic Pearl, and around the same part of the export chain, no flesh browning. So a big varietal difference with very similar, they come in and around the same time and are both white flesh nectarines, but the performance is completely different. And just highlighting a little interesting, in that we've noticed in quite a few trials, take, have a close look at these. This is after 48 hours of ripening and this trend is very similar across importer storage at 12 degrees, actually reduce the incidence of flesh browning compared to the lower temperatures.

And I'll be discussing that more in, in two weeks when I talk about delayed cooling, post-harvest treatments. I won't go into it now, but just something interesting to notice that the higher importer temperature actually reduced incidence of flesh browning.

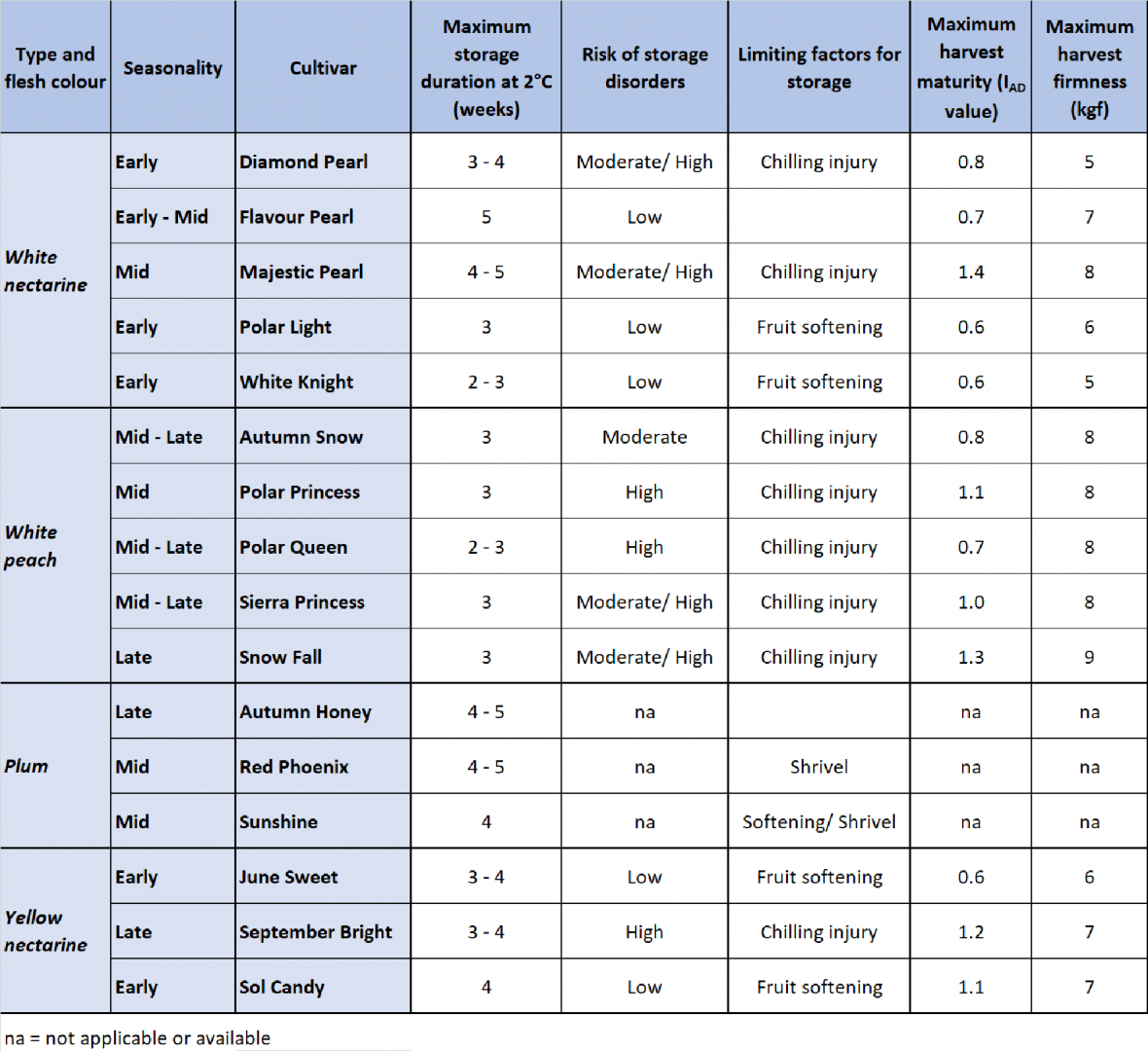

And we have developed a one pager with recommendations about, concerning storage potentials, and cultivars by types of white nectarines, white peach, plum, the ones that we've studied. We provide a sea freight flesh browning or storage is disorder risk. What we consider to be maximum storage duration of two degrees and some limiting factors. And we, Christine will have more information. This is about a year old this spreadsheet, and all this is on an information sheet and we will be updating it, particularly these because we've learned a little bit more about these different varieties, what the maximum storage life is, and it is available on the horticulture industry network websites at the moment. So if you want, if you're interested in understanding sort of the variation between varieties, in terms of storage performance, then this sheet may be useful to you.

Okay. So finishing off that section of the talk. So beyond the service supply chain project, this is what I believe we'd have to look at. I've already started, but potentially new R and D is actually benchmarking our latest new cultivars against best performing varieties. So for example, any new white flesh nectarines would be benchmarked against Flavour Pearl, which seems to be a very good and robust variety, particularly for export. And we could conduct cool storage and ripening trials, as we have, already have. Also optimum harvest maturity based on fruit physiology and yeah, there's always more work to be done there. Post-harvest treatments. I've already started to look at optimum cooling practices after harvest to reduce storage disorders. I'll talk about that, but then there's a lot of modified atmosphere liners, and even half in liners are being used at the moment. And we don't really know the effect of these liners on storage performance. And then the impact of a fumigation for air freight on fruit quality. We've done a little bit of work, but again, a lot more. And with temperature monitoring as Glenn will talk about, issue, we have a lot of data about temperatures, fruit temperatures beyond harvest, but before the freight forwarder, or after sea or air freight, into retail and export markets. Our data's limited so would be interesting to find out more about that. So that's the section on cultivar performance. It is briefly outline and what we've been looking at during the life of this project.

The Serviced Supply Chains project is funded by the Hort Frontiers Asian markets Fund, part of the Hort Frontiers Asian strategic partnership initiative developed by Hort Innovation, with co-investment from Agriculture Victoria, the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries Queensland (DAFQ), Montague Fresh (summerfruit), Manbulloo (mangoes), Glen Grove (citrus), the Australian Government plus in-kind support from University of Queensland and the Chinese Academy of Sciences.